Like all of our trips to the field, it seems when you’re

ready to leave, something comes up, which is why it is so important to be

flexible. We are borrowing a canoe and motor from the NGO that Asher works

with. This is a huge help because it keeps us from having to find a canoe to

rent each time we go to the field. The canoe, we discovered the day before we

wanted to leave, needed some serious repairs. It was leaking and some of the

wood had been damaged by rocks in the river. Our translator spent two days

repairing the canoe to get it back to working order.

Once we finally got on the river, we had a two-day trip

upriver ahead of us. From San Borja, we took an hour-long taxi ride to

Arenales, a Tsimane village with a port where the canoe is kept. We got

everything loaded on the canoe and were on the river by 12 pm.

We made it to Yaranda the first day by 6 pm (sun goes down by 7 pm) and spent the night in the community school. However, the school has quite a few other nightly inhabitants, i.e., bats, lots and lots of bats who like to pee and poop all through the night. Unfortunately, we left our plastic sheets that go over our mosquito net on the canoe, so we were getting bombed all night long, a most unpleasant experience that will not be forgotten any time soon. When we got up in the morning, this little guy was hanging out on Asher’s hat.

We made it to Yaranda the first day by 6 pm (sun goes down by 7 pm) and spent the night in the community school. However, the school has quite a few other nightly inhabitants, i.e., bats, lots and lots of bats who like to pee and poop all through the night. Unfortunately, we left our plastic sheets that go over our mosquito net on the canoe, so we were getting bombed all night long, a most unpleasant experience that will not be forgotten any time soon. When we got up in the morning, this little guy was hanging out on Asher’s hat.

We made it to Anachere by 4 pm the following day, after another

6.5 hours on the canoe.

Our house was not fully complete when we arrived: the walls, roof, beds, and tables were done, but the door and inside walls were not. They finished all of the work within a day of us getting there though, and the house turned out to be even bigger than we thought it would be. With all the supplies for the house, the pay for Dino (our translator) to supervise construction and his passage during October/early November, all the labor (32 work days), and the jatata (what the roof is made from), the grand total for the house came out to just under $800 USD, not bad. It’s our first house, and we’re really excited to be homeowners. The house is a two-bedroom house with a kitchen and outdoor shower and latrine areas. It overlooks the river and there’s papaya and plantain trees in the backyard.

Our house was not fully complete when we arrived: the walls, roof, beds, and tables were done, but the door and inside walls were not. They finished all of the work within a day of us getting there though, and the house turned out to be even bigger than we thought it would be. With all the supplies for the house, the pay for Dino (our translator) to supervise construction and his passage during October/early November, all the labor (32 work days), and the jatata (what the roof is made from), the grand total for the house came out to just under $800 USD, not bad. It’s our first house, and we’re really excited to be homeowners. The house is a two-bedroom house with a kitchen and outdoor shower and latrine areas. It overlooks the river and there’s papaya and plantain trees in the backyard.

Asher brought gymnastic rings down with us, because we're not sweating enough as it is in the jungle:

We also have a tenant that doesn't pay rent:

The house right next to the school, so we have a steady stream of visitors each day when the kids come hang out and watch what we’re up to.

Kelly proud to be a first-time home owner:

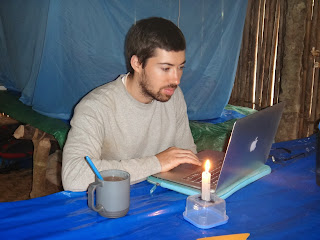

The kids of the Corregidor hang out with us most frequently. They were the closest family and with 15 of them (he has 2 wives) there were many of them around. Many times we would be inside, and they would just open the door and come right in, pointing at the computer and whispering. They loved watching us work – commenting on everything we did. We spent one afternoon giving them a basic math lesson, which turned out to be quite fun, but also quite shocking at the lack of basic arithmetic.

There are a lot of differences between Anachere and Campo

Bello, the close community: namely in Anachere, people are shorter and smaller

and the community is smaller with a more traditional settlement style. Five clusters

of families live in Anachere, but it’s really just 2 families (4 generations).

It’s a 30 minute walk to one cluster where there are 5 families living together.

This isn’t a community in the sense of the word. It’s more like artificial

boundaries grouping people who happen to live nearby together by building a

school. The Corregidor (mayor) complains that the people in the community don’t

really come together. Everyone just kind of lives their own life, unlike Campo

Bello which is much bigger and there are daily soccer games, more nuclear families,

and when a community meeting is called, a good number of people drop what

they’re doing and show up.

The diet in Anachere is much more traditional. While people

rely on the forest and river more for their food – lots of meat from hunting

and fish, they have less diversity (plantains and yucca or corn with every meal)

and some families only eat two meals a day.

Additionally, families in Anachere almost always were making chicha:

A collared peccary:

A smoked monkey:

A family eating a soup made with the monkey:

Additionally, families in Anachere almost always were making chicha:

People in the community also were much more willing to trade food with us, trading freshly caught fish, papayas, plantains, and bananas for dietary staples we brought with us.

Early in the trip, we went on a focal follow into the monte (old growth forest) to see one of the men cut down jatata, a thatch palm, and what he does for water when he goes to do this. People spend a lot of time going into the old growth forest to extract jatata. It varies between a 1- and 2-hour walk each way. However, with such a long walk, people don’t really bring water with them. Instead they rely on getting water from streams or two different vines that are full of water (vehucos): Ona de gato and cayaya. They take a machete to the vine, and drink directly from it. We cut a meter and a half piece and measured the amount of water in it (300 ml of water), and Dino, our translator told us that since it had been dry for the last several days, there was less water in it than there usually would be. We tasted the water, and it tasted pure with a bit of a barky taste.

One of the men in the community and Dino making jatata - thatch palm for roofing (how all the people in the community make money/trade for food):

While the views were beautiful of the river, we didn’t spend

much time on the beaches as the sand flies were out and about, and they leave

really nasty bites where blood clots. We both ended up getting covered in bug

bites despite wearing long sleeves and pants and using bug repellant, which

these mosquitos don’t seem to mind. There are a lot of bugs upriver, especially

in the rainy season.

And it is definitely the rainy season here. One night we got

5 inches of rain in less than 10 hours and two other days we got more than 2.5

inches in 24 hours each time.

It was incredible how much rain can fall here: in the 3 weeks we were there, we got ~13 inches of rain. It’s like we’re in a freaking tropical rainforest. The river swollen after a rainstorm: debree and logs floating in the current:

But it was also incredible how fast the ground dries. There would be more than 2 inches of rain pooled on the ground and within 5-6 hours, it would be dry.

It was incredible how much rain can fall here: in the 3 weeks we were there, we got ~13 inches of rain. It’s like we’re in a freaking tropical rainforest. The river swollen after a rainstorm: debree and logs floating in the current:

But it was also incredible how fast the ground dries. There would be more than 2 inches of rain pooled on the ground and within 5-6 hours, it would be dry.

The trip also had a lot of ups and downs, like any trip. A

little more than a week into the trip, the interviews were going really well. Asher was getting a lot of different information than he was getting from Campo Bello. We woke

up to really hard rain on the morning of Friday the 13th, Asher's brother’s 32nd birthday, and as we were discussing which house to

visit, Dino tells us that he just got a radio message from his brothers that

his mother is seriously ill and that he needs to go back to San Borja. This

left us in a bit of a conundrum as he needed to take our canoe with the motor,

and he was going to take the mayor with him. We wanted to be accommodating, so we

said yes, and he said that the son of the Corregidor who spoke some Spanish

would help us while he was gone for four days (one day on the river, one day in

SB, and 2 days coming back). We didn’t really consider at the time since it all

happened very fast what we would do if we had an accident (with no canoe and

motor and no one who spoke Spanish very well). This is especially important in

the Anachere since we’re so far from San Borja and fewer people speak Spanish. We

were particularly concerned since we saw 2 vipers (nas) within 3 days, one very

large one in the path where we walk almost daily. Anyway, when we went to the

corrigedor’s house later in the day, it turned out that the son who spoke

Spanish went with them in the canoe, and there was no one in the community left

who spoke Spanish. So not only could we

not do any research, we had no one to talk to if we did have an emergency.

Lesson learned: if we are upriver and any emergencies arise, we will all leave

or none of us will leave. Dino ended up getting stuck in San Borja two extra

days because of heavy rainstorms, so we ended up being alone in Anachere for 6 days. We

stayed together and took extra care getting water (the riverbanks are very

slippery) and doing other chores to stay safe.

When Dino got back, the research was back on track. We were

getting some really good interviews and data.

However, the third to last night someone came into our house and stole 2 packs of pasta, 1 can of sardines, and 1 bag of lentils. We had enough food, but it was disconcerting that someone came into the house while we were sleeping and took some food. Later that day, as we were on the canoe trying to start the motor to get to an interview, we discovered that the sparkplug for our motor was also stolen. This theft was incredibly inconvenient as this $5 item meant that we went floating down the river. With Dino’s skilled navigation, we were able to grab onto a tree in the river so that we wouldn’t keep floating down – a bit of a scare. Dino climbed the cliff and got our spare sparkplug that he said was not functional but would give it a try nonetheless. After cleaning it and trying it for a while, he finally got it to work. Another lesson learned: never leave your sparkplug in your motor.

However, the third to last night someone came into our house and stole 2 packs of pasta, 1 can of sardines, and 1 bag of lentils. We had enough food, but it was disconcerting that someone came into the house while we were sleeping and took some food. Later that day, as we were on the canoe trying to start the motor to get to an interview, we discovered that the sparkplug for our motor was also stolen. This theft was incredibly inconvenient as this $5 item meant that we went floating down the river. With Dino’s skilled navigation, we were able to grab onto a tree in the river so that we wouldn’t keep floating down – a bit of a scare. Dino climbed the cliff and got our spare sparkplug that he said was not functional but would give it a try nonetheless. After cleaning it and trying it for a while, he finally got it to work. Another lesson learned: never leave your sparkplug in your motor.

Asher wasn’t able to get all of the interviews he wanted due

to these unforeseen circumstances, but we had a good trip upriver. Us with one of the larger households - they actually asked for us to be in the picture with them and put the sirai (the Tsimane' handbag) on Asher. Then when the looked at the picture all laughed and said sirai Asher.

We finished the trip on the 23rd, getting up at 5 am and loading the canoe as it started raining. We got on the river a little before 8 am. We had really good weather for the trip back, only one hour of rain, and by 1:30 pm we were back at the port in Arenales.

We finished the trip on the 23rd, getting up at 5 am and loading the canoe as it started raining. We got on the river a little before 8 am. We had really good weather for the trip back, only one hour of rain, and by 1:30 pm we were back at the port in Arenales.